The Brave New World of Corporate Venturing. Part I: The Traditional Models

Every established organization must be willing and able to systemically deal with value shifts, or risk missing the next big thing. Value shifts come in many shapes and forms, from consumer preferences, technology developments and competitive market dynamics. Sometimes, organizations can anticipate, even create game-changing value shifts, other times, they can only realistically hope to notice shifts in time to formulate a quick reaction.

Mechanisms to Deal with Value Shifts

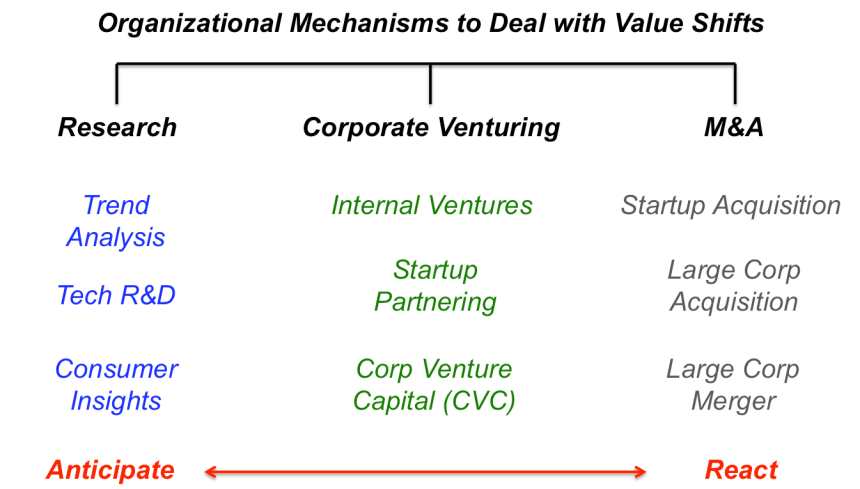

The corporate mechanisms to systemically anticipate and react to value shifts are generally divided into three major categories (See Fig 1):

- Research

- Trends/Scenario Analysis

- Technology R&D

- Consumer Insights

- Corporate Venturing

- Internal Ventures

- Startup Partnering

- Corporate Venture Capital

- Mergers & Acquisitions

- Startup/SME Acquisitions

- Large Corporate Acquisitions

- Large Corporate Mergers

Figure 1:

The mechanisms to deal with value shifts listed above are the innovation levers of the organization’s leaders, starting with the CEO and often including the CTO, CMO, CSO, and more recently, the CINO (Chief Innovation Officer). The levers are tailored to different time horizons in the ‘Anticipate to React’ continuum. Most large corporations have some version of each of the specific mechanisms listed below the three major categories, albeit ranging from a systemic and advantaged capability perfected over the years to an ad-hoc process as the preferred ‘way of doing things’. Each of the mechanisms can be directed to sustaining success in the ‘current core markets’ in which the organization operates and/or directed to unraveling ‘new to the organization’ and ‘new to the world’ opportunities. That is dictated by the organization’s given growth strategy, not the mechanisms themselves.

The Role of Corporate Venturing

In this blog, I focus on the corporate venturing mechanisms, which in general help an organization ‘translate’ its research and point of view endeavors to new, profitable business models (either organically and/or inorganically). It could be argued that corporate venturing is especially needed to help and organization navigate market uncertainty, but it also helps to reduce technical uncertainty in areas in which the company has little to no experience (and where others are on the cusp of commercialization).

Corporate venturing is especially needed to help and organization navigate market uncertainty, but it also helps to reduce technical uncertainty in areas in which the company has little to no experience.

Traditional Corporate Venturing Models

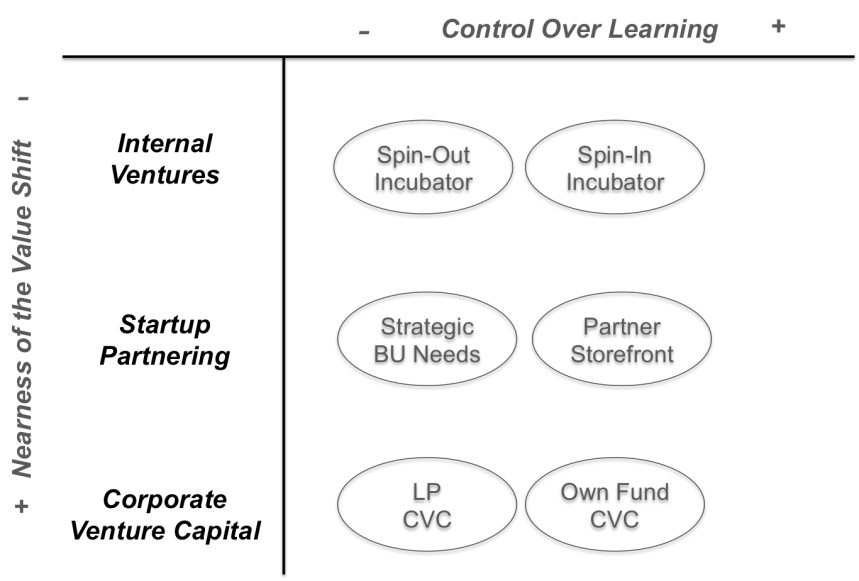

Corporate Venturing models have been around for a relatively long time, ever since corporations started thinking of launching new ventures from within and/or started paying attention to the startup activity in respective ecosystems of interest. Traditional corporate venturing models can be mapped along two dimensions: The ‘nearness of the value shift’ they are tailored to seize and the degree of ‘control over learning’ that the organization desires (See Fig 2):

- Internal Ventures

- Spin-Out Incubator

- Spin-In Incubator

- Startup Partnering

- Strategic Business Unit Needs (Ad-Hoc)

- Partner Storefront

- Corporate Venture Capital

- Limited Partner CVC fund participation

- Own CVC fund

Figure 2

The traditional corporate venturing models still serve their purpose, but are increasingly coming under pressure to deliver results as stand-alone units in an ever changing world of cross industry value-shifts and opportunities. Each of the models is described in detail below:

The Internal Ventures Models (Spin-Out & Spin-In Incubators) make sense in situations where an organization spots a commercial opportunity before the startup/VC community (perhaps as a follow-on to an internal R&D project), but those situations are becoming fewer and further in-between in a world of opportunities driven by digitalization, the Internet of Everything (IOT) and artificial intelligence, where the startup/VC engine continues to hum along. Furthermore, Internal Ventures teams are increasingly tasked with devising platform vs. single product strategies, which by definition require some deeper understanding and probable stimulus of an accompanying ecosystem of developers, startups and other corporate partners, usually the tasks of the other CV models.

By definition, internal venturing models offer a high degree of control over activities, but come with an increasing risk of execution and risk of missing better opportunities.

By definition, these internal focused models offer a high degree of control over venturing activities, but come with an increasing risk of execution and risk of missing better opportunities. A fairly recent twist on internal ventures has been the incorporation of employee or consumer ideas as an open, front-end feeder system (idea crowdsourcing) – an improvement to reducing the waste of working on the wrong ideas, albeit bringing structural and incentive challenges to follow-up, involving idea originators in execution and dealing with ‘not-invented-here’ syndrome.

Organizations that have a long history with internal ventures, usually following the customary advice of running them separate from the core businesses, include Philips, Intel, Cisco, HP, Alcatel-Lucent, Medtronic and P&G.

The Startup Partnering Models (Strategic BU Needs & Partner Storefront) make sense in situations where an organization has defined specific business or technical problems that can be solved through startup (&/or SME) relationships. The Strategic BU Needs model is an ad-hoc, distributed process of external partnering driven by a particular operating business unit to fill its specific need. It often involves the bundling of a large organization’s product or platform with a startup’s product or IP component to solve an existing customer’s problem (usually the large organization’s customer). The Partner Storefront model is a centralized version of the previous model, inviting a wider array of potential partners to either compete to solve a well-defined corporate challenge and/or build their businesses atop a predefined corporate business platform. (Partner storefronts rarely, but sometimes encourage ‘unsolicited’ ideas from startup & SMEs as long as the ideas are patented and the storefront’s staff is equipped to deal with the added ‘noise’).

Startup partnering is ‘strategic’, but as a stand-alone effort, risks being too conservative.

Traditionally, startup partnering efforts are ‘strategic’, i.e. further an existing bet or hypothesis to a value-shift, but as stand-alone efforts, risk being too conservative, serving short-term P&L objectives of under-pressure business unit or platform managers vs. long-term growth objectives set by a more patient corporate c-level management team. Furthermore, when motivated by ad-hoc, short-term needs, startup-partnering activities take on a transactional nature (matching of what both parties already know, built and own) vs. a true, long-term strategic partnership nature that can uncover a host of unknowns and new opportunities, IP and solutions benefiting both parties.

Most ‘system integrator’ organizations have a long history with startup or SME partnerships driven by business unit or existing platform managers including Microsoft, GE, GM, Ford, Qualcomm, J&J Janssen and Facebook (Some of them have been evolving their model to what I later describe as ‘Sponsored Acceleration’).

The Corporate Venture Capital Models (LP CVC & Own Fund CVC) make sense in situations where an organization has spotted an innovation arena characterized by a swarm of startups, well-funded startups, I may add (yes, the corporation needs the validation and financial support of the financial and corporate VC community, it cannot place itself as the startups’ sole believer and savior). The Limited Partner CVC model entails investing in an existing financial VC fund, not directly in startups (it trades control over investments and learning with having to form an internal CVC unit). A new twist on this model is investing in seed-fund accelerator VC’s and having a ‘special seat’ at the table during startup progress reviews and demo-days. The Own Fund VC model entails investing directly in startups, justifying the extra effort and expense of carrying an internal VC unit for additional control over the investment decisions and learning process. A new twist on this model is forming joint-funds with other non-competing corporations to best assess a cross-industry investment arena.

The primary justification for CVC is superior ‘market intelligence’

Traditionally, the primary justification for CVC models is superior ‘market intelligence’ – having a finger of the pulse of a budding growth opportunity by being directly connected and highly engaged with the startup and VC community. But traditional CVC models suffer from a couple of structural challenges. Firstly, a CVC fund is not a blank check from the corporate treasury. Corporate LPs or GPs of the fund are under pressure to produce a return on invested capital, despite their ‘strategic’ focus. Balancing strategic with financial objectives can be a difficult task, and it can lead to becoming ‘self serving’ (worrying more about the survival of the fund that finding the next big opportunity for the parent company). Secondly, it can be hard to translate the attained ‘market intelligence’ into a new growth opportunity for the company, especially a ‘non-strategic’, new growth opportunity – meaning, the CVC fund wasn’t merely used to prop-up a given platform’s ecosystem of startup partners and actually helped to create a new business model by itself (through an eventual startup collaborative effort or out-right startup acquisition), even if that new business model threatens the current core business.

Organizations with significant commitments to Corporate Venture Capital models include Google, Intel, Qualcomm, Novartis, GE, Samsung, J&J, Siemens, Citi, MS and Disney. Google seems to lead the pack in terms of non-strategic CVC activity (in their case, things completely unrelated to web search). Qualcomm and Novartis have started a joint-fund in digital pharma (and likely opening to others).

Conclusion of Traditional Corporate Venturing Models

Traditional corporate venturing models have long been in use by corporations looking for ways to deal with value shifts in that murky middle ground between Research and M&A activity. These models can be classified into Internal Ventures, Startup Partnering and Corporate Venture Capital. Most large corporations have a systemic approach to these activities, meaning they have a structured format to operate each or some of the described models (combination of stated objectives, procedures, funding, staffing, governance, etc.).

Some large corporations still prefer the ad-hoc way to deal with the end-goals of each of the models – for example, they assemble an internal venture to pursue an unexpected opportunity, they partner with startups on rare occasions where internal teams rather redirect their development efforts elsewhere or they invest in startups without a pre-determined, earmarked fund when it suits their craving for learning and connecting to a new ecosystem.

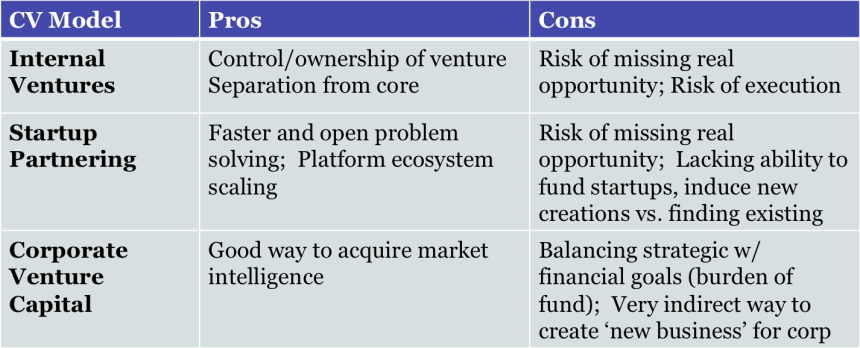

As described above, operated as stand-alone efforts, each of the traditional corporate venturing models has salient pros & cons (See Fig 3):

Figure 3

The overall issue with these traditional corporate venturing models is that they were invented when the world of innovation was frankly, a lot simpler. Value Shifts occurred within traditional industry boundaries and they were characterized by discrete customer, technology or competitive issues, not a messy combination of each. Linear R&D could be translated into relatively straight-forward new adjacency markets, partnerships could be used to fill gaps in product lines or components and venture capital could be used to learn surely but slowly, often a simple insurance system, just in case the large corporation was ‘missing out on something’.

The overall issue with these traditional corporate venturing models is that they were invented when the world of innovation was frankly, a lot simpler.

Turns out that things have stepped into overdrive. Value shifts occur at the intersection of industries and bring a mix of consumer wants, technologies and unexpected new entrants. Few opportunities arise from simple ‘tech-push’ R&D without accompanying business model innovation. Partners are no longer content as glorified vendors and want equal exchange of value and the collaborative pursuit of new things themselves. Corporate venture capital must help create new markets and become a direct line to the company’s new lines of businesses, not simply a listening station or a self-serving P&L.

In this brave new world of innovation, the traditional corporate venturing models must evolve to meet the new challenges of the corporation, work in unison, not as separate silos and ultimately give rise to entirely new, superseding structures that can deliver total, continuous innovation, not a patchwork of inconsequential accomplishments. I will discuss the budding evolution and eventual revolution in corporate venturing models in the next post.

Pingback: The Brave New World of Corporate Venturing. Part II: Emerging Models | Necrophone

Pingback: The Brave New World of Corporate Venturing. Part III: Tugboat Venturing | Necrophone